(Published in the South China Morning Post on 15 October 2006)

In a November 2005 report, James Montier, the maverick global equities strategist for investment bank Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein in London, identified seven deadly sins of fund management. For that matter, they apply just as well to any investor.

In a November 2005 report, James Montier, the maverick global equities strategist for investment bank Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein in London, identified seven deadly sins of fund management. For that matter, they apply just as well to any investor.

They are: poor forecasting; being fooled

by the illusion of knowledge; being mesmerised by company management; believing

you can out-smart everyone else; short-time horizons and over-trading; believing

everything you read; and group think.

In varying proportions, he argued,

they were all responsible for the poor decision-making that leads to unhappy

returns. The performance of funds, after all, or any investment portfolio, is

the result of a series of buy and sell decisions. The fact that around 70 per

cent of actively traded funds does worse than their benchmark indices suggests that

the average fund manager may actually be hardwired to make poor decisions.

In fact, research suggests this as well.

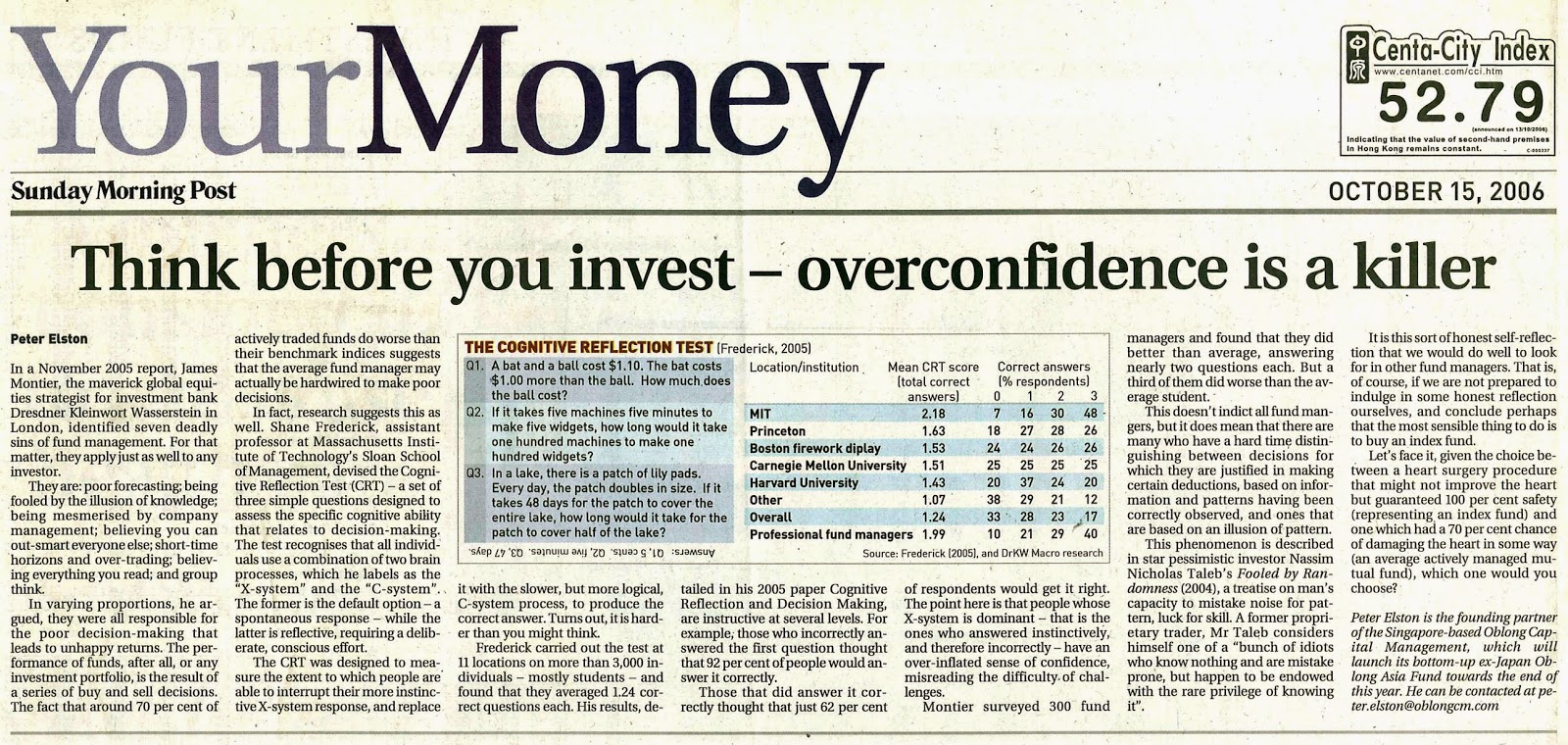

Shane Frederick, assistant professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology's

Sloan School of Management, devised the Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT) — a set

of three simple questions designed to assess the specific cognitive ability that

relates to decision-making. The test recognises that all individuals use a combination

of two brain processes, which he labels as the "X-system" and the

"C-system". The former is the default option — a spontaneous response

— while the latter is reflective, requiring a deliberate, conscious effort.

The CRT was designed to measure the

extent to which people are able to interrupt their more instinctive X-system

response, and replace it with the slower, but more logical, C-system process,

to produce the correct answer. Turns out, it is harder than you might think

(see the original at the bottom of this post for the test questions and answers).

Frederick carried out the test at 11

locations on more than 3,000 individuals — mostly students — and found that

they averaged 1.24 correct questions each. His results, detailed in his 2005

paper Cognitive Reflection and Decision Making, are instructive at several

levels. For example; those who incorrectly answered the first question thought that

92 per cent of people would answer it correctly.

Those that did answer it correctly

thought that just 62 per cent of respondents would get it right. The point here

is that people whose X-system is dominant — that is the ones who answered

instinctively, and therefore incorrectly — have an over-inflated sense of

confidence, misreading the difficulty. of challenges.

Montier surveyed 300 fund managers

and found that they did better than average, answering nearly two questions

each. But a third of them did worse than the average student.

This doesn't indict all fund mangers,

but it does mean that there are many who have a hard time distinguishing

between decisions for which they are justified in making certain deductions,

based on information and patterns having been correctly observed, and ones that

are based on an illusion of pattern.

This phenomenon is described in star

pessimistic investor Nassirn Nicholas Taleb's Fooled by Randomness (2004), a

treatise on man's capacity to mistake noise for pattern, luck for skill. A

former proprietary trader, Mr Taleb considers himself one of a "bunch of

idiots who know nothing and are mistake prone, but happen to be endowed with

the rare privilege of knowing it".

It is this sort of honest

self-reflection that we would do well to look for in other fund managers. That

is, of course, if we are not prepared to indulge in some honest reflection ourselves,

and conclude perhaps that the most sensible thing to do is to buy an index

fund.

Let's face it, given the choice between a heart surgery procedure that might not improve the heart but guaranteed 100 per cent safety (representing an index fund) and one which had a 70 per cent chance of damaging the heart in some way (an average actively managed mutual fund), which one would you choose?

Let's face it, given the choice between a heart surgery procedure that might not improve the heart but guaranteed 100 per cent safety (representing an index fund) and one which had a 70 per cent chance of damaging the heart in some way (an average actively managed mutual fund), which one would you choose?

No comments:

Post a Comment